2007

Journal Publication

Annual Review of Genetics

Cell Turnover and Adult Tissue Homeostasis: From Humans to Planarians

Pellettieri J, Sánchez Alvarado A

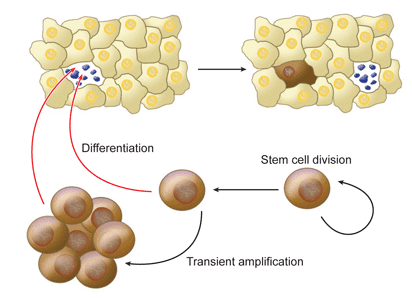

For many organisms, including humans, the relatively constant outward appearance of adult individuals belies an ongoing inner transformation. In fact, it is this internal change that paradoxically enables maintenance of the anatomical status quo, or tissue homeostasis. One critical mechanism preserving form and function in developed tissues is the conceptually straightforward yet poorly understood process of cell turnover. Simply stated, certain differentiated cells are regularly eliminated and replaced by the division progeny of adult stem cells. In humans, the magnitude of this flux is truly astounding it has been estimated that each of us eradicate and, in parallel, generate a mass of cells equal to almost our entire body weight each year. Thus, it is only through constant change that we in so many ways remain the same. The two basic parts of the cell turnover equation, cell death and cell division, have been researched and reviewed extensively over the last several decades. Although this body of work has provided great insight into each of these individual processes, we know very little about how cell death is integrated with cell division, particularly during the self-renewal of adult tissues. The purpose of this review then, is to highlight several fundamental, but largely unanswered questions about the regulation of cell turnover and its role in fully developed organisms. We advocate using the experimentally accessible freshwater planarian Schmidtea mediterranea as a model system to begin addressing these questions. Before turning to these areas, however, we must first define some key terms and review some basic concepts of adult tissue dynamics.

Address reprint requests to: Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado